Understanding player types & motivations in web3 gaming

Novel player types have emerged through open economies in web3 gaming. Understanding their motivations & impact through analytics will be crucial for successful developers.

“Focused on fun”.

“Fun comes first”.

“Find the fun”.

After riding the last wave of “play-to-earn” and “GameFi” to new heights (...and all the way back down again), many investors and commentators have now turned to mantras such as these when speaking about the differentiating factor for game developers’ future success. It seems obvious, at first glance: shouldn’t all games be about having fun?

Where these platitudes fall short is not in their truthfulness, but in their sweeping generalizations. In practice, the experience of “fun” varies widely from one gamer to the next. It may even change from one game to another for the same player! Grand strategy games offer different forms of fun than fast-twitch fighting games, for example, yet one person may still enjoy both genres deeply.

Rather than fixate on “fun” as a means of classification, game developers have typically relied upon different motivational personas to explain why players behave the way they do: why they choose to engage with some games and not others; why they play those games alone, or with friends; and even why they do or do not spend money in a given game.

We believe that understanding web3’s novel player personas and their motivations is in fact the differentiator for building successful games, so let’s get into it.

Moving Beyond “Fun”

One common framework for examining these various player motivations is the Bartle taxonomy of player types, popularized by British games researcher Richard Bartle for use in role-playing games.

Bartle’s Four Player Types. Image Credit: Galaxy Digital

Each of Bartle’s four player types represent different motivations for playing games. For “Achievers”, video games are about accomplishing goals and earning rewards. They are motivated by a sense of progress and the feeling of satisfaction that comes from completing tasks. “Socializers”, on the other hand, relish the opportunity to make new friends and collaborate with others.

These are just a few examples of the use of motivational segmentation in gaming. The Bartle framework is quite common, but a variety of other approaches are in use across the games industry today. In some cases, large publishers have developed their own models, best applied to games within their portfolios or others operating in their target genres (e.g., casual games, midcore mobile games, etc.). Elsewhere, new startups are creating bespoke models, servicing smaller developers that might not have the resources to support their own internal user experience research groups.

Despite the frequency of its application in a variety of gaming contexts, motivational segmentation as it exists today is still underdeveloped as a way to drive successful engagement and monetization in web3 gaming. The integration of blockchain technologies and the introduction of open economies to gaming has given way to a variety of new and unusual motivations not typically seen in traditional games. This requires a rethinking of the problem and a novel approach to motivational segmentation – something that we here at Nami see as key for successful web3 games.

Player Behavior in Open Economies

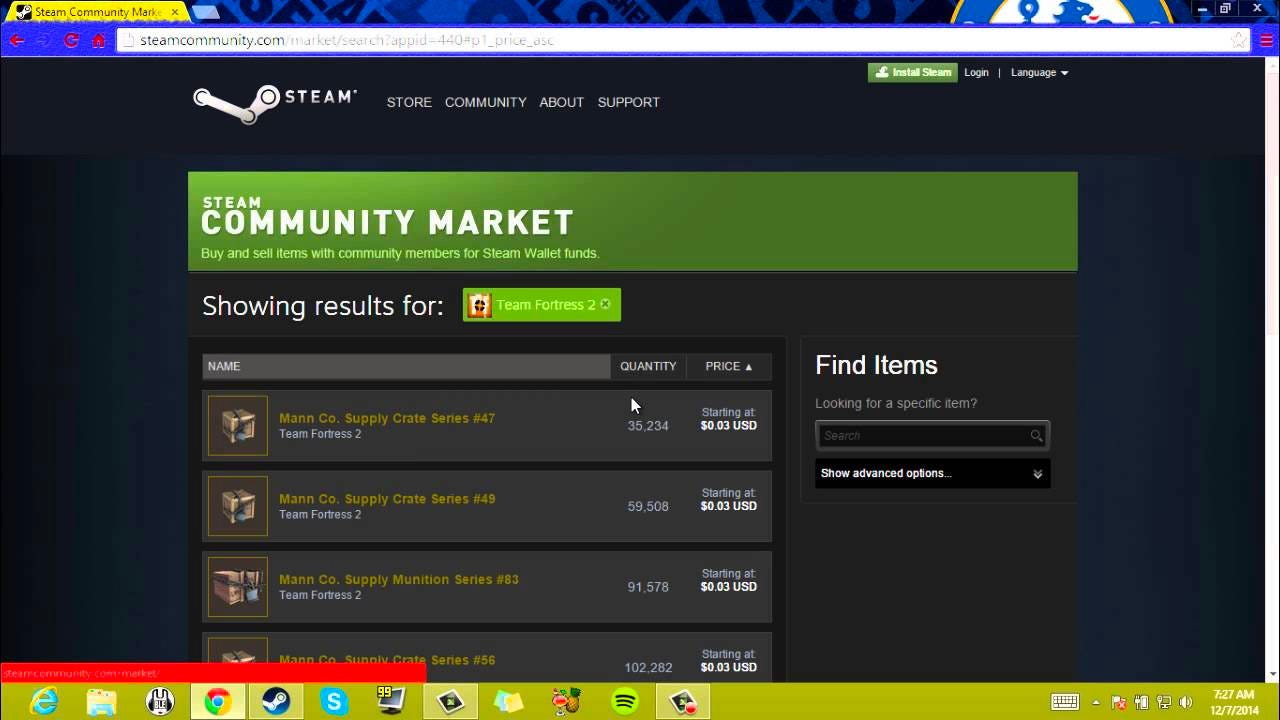

Before we dive deeper into the peculiarities of player motivations in web3 gaming, it’s worth taking a brief look at historical parallels to game economies in the pre-blockchain era. Open economies and player ownership are not entirely new concepts, as we have previously seen concepts such as player-to-player trading, virtual land sales, and yield farming take place in some of the most popular MMOs of all time (think World of Warcraft, Second Life, or EVE Online). The key differentiation, of course, is that all of this economic activity happened within the confines of the game itself. Valve pushed these concepts further by introducing the Steam Marketplace, but this was again constrained to a specific ecosystem, allowing nothing to be sold directly for real money – just Steam money.

Steam Community Market. Image Credit: YouTube

The ability to build a system that allows for decentralized and unrestricted trade outside of any one game – or even across multiple game ecosystems – is unique to web3. Blockchain technologies allow for permissionless financial ledgers to operate independently, enabling exchange of assets without requiring the permission of any game or app. This has given rise to multiple new behaviors and motivations not previously captured by the Bartle taxonomy or other similar methodologies.

In the pre-web3 era, online games were primarily a vehicle for monetization. In the web3 era, however, players have many different motivations to participate in game ecosystems, even after losing interest in the underlying game itself – a lot of them are tied to the economies within the game.

Many of the new player motivations seen in web3 gaming are related to the unique financial models brought about by externally verifiable ownership of digital assets; in other words, the ability for stakeholders outside of the game’s development team to track down ownership and chain of custody via the blockchain’s transparent immutable ledger. The most common and public example of this thus far has been asset speculation; in other words, buying up game tokens with the hope that they will appreciate in value. However, speculation is but one of several new motivations enabled by web3 gaming.

Verifiable ownership, chain of custody, and market making for digital assets impacts many different gaming behaviors (and enables a few new ones, too). Earning money from playing games, for example, is no longer restricted to esports pros and top-tier content creators. An entire “Play-to-Earn” / “Play-and-Earn” space has sprung up around web3 gaming. Sustainability questions aside, the ability for players to extract value from a game creates an entirely new set of motivations and associated behaviors that would never exist in traditional games.

Image Credit: Nami

Even beyond extracting the value of a game asset, verifiable ownership also allows for trustless and permissionless sharing of value. Suppose a player acquires a game asset – say, an ultra-rare character. The most commonly discussed use case (beyond playing with the character in the game) would be to sell it to another player. This may be associated with financial speculation, or it may allow the player to recoup some of their previous investment (of time or money) into the game, similar to selling a pre-owned copy of a physical game disc back to a retailer. The player might also choose to loan the character to other players (rather than sell it outright) and collect passive income. Alternatively, they might choose to fractionalize the asset, sharing ownership with a group of fellow players or investors.

From a developer standpoint, the new properties of digital assets enabled by web3 can be leveraged to tap into other player motivations. One such example is the desire for collection or completionism. With verifiable ownership and provable scarcity, players can pursue rare items to complete their collections (either directly by playing the game, or indirectly via trade with others), to display their prestige (both in-game and out-of-game, via web3 wallets or NFT exchanges), or even to show off their fandom (by seeking out items previously owned by their favorite streamer or esports pro, for example).

Understanding novel player motivations and their impact on game economies is crucial for game developers, yet there is a lack of definitive guides or tooling for analysis and optimization. This is where Nami comes in, offering products and solutions to this challenge.

Understanding Player Personas in Web3 Gaming

These are just a few examples of how blockchain technology can influence player behaviors in new and interesting ways. When pairing in-game analytics with a clear picture of on-chain activity, game developers can elevate their understanding of their player base and craft novel experiences that uniquely tap into players’ underlying motivations and build more successful games. This is precisely what we are building at Nami.

Identifying some of the following player archetypes in a game allows developers to better understand the fabric of their game economy and tailor incentives accordingly. As this framework is constantly evolving, we welcome any feedback and encourage you to get in touch.

The Profit-Maker

The ability to trade in-game currencies and items for real currencies means that players can now calculate a financial ROI or profit. For the player, intrinsic motivations like “this game is fun” and “this game is challenging” are replaced by extrinsic motivations like “I can make money by playing”. A game with a well-designed economy can convert financially motivated retail speculators into deflationary players for the game’s economy.

While some amount of speculation is to be expected – there will always be players who love to optimize – the majority of players cannot have an expectation of profit in order for the game to remain sustainable. Pegaxy is a great example of a game driven primarily by profit-seeking with little actual gameplay; essentially, it’s just gambling.

The Collector

Humans are hoarders by nature, and many carry this trait with them into virtual worlds, as well. There has always been a subset of players obsessed with collecting things in games, but the relevance and value of these collections have been restricted to the game and could only be shared via screenshots or videos.

Since items cannot be traded in such closed ecosystems (outside of some limited examples), many players were left with incomplete collections that they could not display publicly. With NFTs, however, players can now access tradable assets with provable rarity, issuance, and ownership. This attracts players who are more passionate about collecting game assets rather than solely playing the game.

Collecting is by far one of the most sustainable motivations for players to have because it is generally focused on spending and not profit, with the ability to scale up as more content is added to the game. This behavior is also not dependent on the number of players actively playing the game. Trading card games like Splinterlands do a great job of this by heavily encouraging and rewarding a broad collection through its gameplay rules.

The Early Believer

A digital asset pre-sale prompts players to invest money into a game ahead of its launch in exchange for some form of in-game bonus, which they receive upon the game’s release. Notably, this is not unique to web3 – traditional game publishers have long offered pre-sales that conferred various in-game bonuses – but the ability to pre-sell items as NFTs (or organize NFT mints) allows developers to give future players an asset that they can opt to keep or trade. Not only does this enable passionate game fans to fund their favorite games’ development, but it also allows game NFT investors to make decent profits by reselling NFTs to later fans.

Game economies can handle this type of activity in moderation, but it’s wiser to avoid investment or profit-seeking motives where possible. A better approach would be to align pre-sale perks with player motivations through benefits like early access, special collectors genesis editions, or other non-financial rewards. Crypto Unicorns is one example of a game that did well in early sales, but quickly saw prices drop due to the slow pace of actual game development. These falling prices tend to lead to negative feedback loops of players losing interest in the game (or worse, losing trust in the developers), thereby causing prices to fall further, and so on.

The Big Spender

Ordinarily, pay-to-win games are designed so that game developers can profit from sales of in-game currency or items that provide an advantage within the game. A small subset of players who make high volume in-game purchases (often referred to as “whales”) make up a large part of a game’s revenue.

Open economies create a channel for regular players to also profit from these big spenders. The combination of artificial scarcity, pre-sales activities, and interoperability enables players to invest and trade in-game assets that are in demand. For example, if you own a rare potion, you can potentially sell that item to a pay-to-win player for real money. This behavior is reminiscent of trading card investors who exploit rarity to generate profits through secondary market sales — regardless of whether or not they play the game. Having an active economy for game assets also allows players to exit a game while recovering some of their investment (both time and money) by selling their items to other players.

It’s typically a good idea to both support and mitigate players looking to spend heavily by utilizing game balance changes to keep the game’s meta shifting ever so slightly. This leads to a fluctuation in the value of purchases, but not so much that heavy spenders feel burned. Axie Infinity has seen a fair bit of this due to the metas at different ranks utilizing certain Axie genes, which in turn determine the cards available, and ultimately, their price.

The Rent Taker

Most game genres (except perhaps idle games) require you to play the game to accumulate game assets. In web3 games and DeFi-inspired game ecosystems, asset owners can earn passive rewards and yield via the renting or staking of assets. This goes for playable assets like trading cards or characters, as well as geographic assets like virtual land.

Metaverse games like Decentraland allow players to rent out land NFTs. Image Credit: Decentral.Games

This motivates players to rent out or stake assets they are not actively using. Axie Infinity, for example, had an entire guild economy centered around passive income generation where cash-rich and time-poor Axie owners rent out their Axie NFTs to time-rich and cash-poor scholars to earn passive income.

While passive income generation seems like a good idea for increasing game developer revenue upfront and putting the economy “in the hands of the players”, it also has the unfortunate side effect of recreating some of the worst aspects of capitalist systems. There have been various methods proposed for properly taxing these sorts of assets (e.g., through land value tax schemes), but they are generally much more complicated than most games will want. Axie Infinity, for example, has painted itself into a corner with pre-sales of land NFTs that now require a sustainable use case that doesn’t also distort the rest of the game economy or overly inflate the AXS token.

The Rarity Hunter

While non-web3 games may have rare assets, there is no transparency as to the level and extent of rarity. Additionally, this rarity is relevant only within the context of that specific game; for instance, a person who does not play CS:GO would likely not care about a rare gun skin from that game.

Web3 solves this problem with smart contracts, which add a layer of transparent verifiability to digital assets, removing the need for them to be constrained to a specific closed ecosystem. This, combined with the ability to dictate rarity via code, allows for a system of value from scarcity that previously existed in less liquid environments (e.g., collectors’ items with mint numbers or extremely low print runs). This provable uniqueness has led to players valuing the rarity of the asset more — both economically and socially. However, the scarcity of these assets can also distort games when it comes to players monopolizing limited content or limiting player growth.

Players motivated by artificial scarcity might be genuine players, investors, rabid fans, collectors, or even random NFT degens. Whatever the case, it’s important to ensure that genuine players and collectors make up the majority of your player base, or else scarcity will start backfiring. At times, Axie Infinity suffered from this in its early days due to the bottleneck of breeding and distribution (or lack thereof). Eventually, the inflated costs of the limited Axies available lead to overbreeding and huge drops in financial returns.

The Hodler

True ownership also means a stronger sense of loss. Since NFTs can sometimes require significant capital to acquire, players will naturally try to make a profitable exchange out of it. This combination of sunk cost fallacy and loss aversion can lead to higher-than-expected retention rates for web3 gamers. Many developers in the space have reported that many players do not actually play their game; instead, they end up passively holding NFTs for various reasons (collecting staking rewards and potential token airdrops, in-game events, access to the community, speculating a higher price, etc.).

In general, it's best to have a player base that is actively seeking to play with their assets. However, if there is a limited supply of them then developers should encourage inactive players to sell to new players that may retain better. Splinterlands, for example, has had fairly high retention of players either playing the game or at least renting out their assets to other new players to keep the flow of older cards available for play.

Card rentals in Splinterlands. Image Credit: PeakD

Monitoring and understanding these various player behaviors is a powerful unlock for game developers. The studios and teams that learn to leverage this information actionably will be among the first to create the next generation of the most successful open game economies.

The Road Ahead

Web3 gaming has attracted a lot of talent and investment, with many executives from web2 corporations moving to the space and over $4.1B invested in the first half of 2022. However, despite these developments, web3 gaming is still in its early stages. For instance, there are currently around 2,000 blockchain-powered games, compared to over 1 million games on Apple's App Store alone. This illustrates that there is still a long way to go before web3 gaming reaches mass adoption.

One of the main challenges for web3 game devs is the complexity of managing an open economy. It is easy to assume that players just want to have fun, but in the context of web3, ancillary behaviors can have a significant influence on players' experiences, even for traditional gamers. This is why it is imperative for game developers to pay as much attention to economic design as they do to gameplay. As the industry enters its next phase, there will be a greater need for tools that help game developers deeply understand, efficiently manage and successfully build game economies.

At Nami, our goal is to empower game developers to leverage the behavioral and economic peculiarities of web3 gaming by using analytics across their entire game development cycle. Specifically, our tools provide actionable insights for the most important and exciting efforts in game development: understanding, acquiring, retaining and monetizing users. Armed with this knowledge, game designers, product managers, and data analysts leverage Nami to make better business decisions and align more closely with their player base, resulting in a healthier game economy and community.

Additionally, from the earliest stages of your development journey, our team of gaming-specialised consultants leverage our market and user analytics tools to help you build successful and sustainable games.

We are dedicated to proliferating the use of analytics in web3 gaming and are proud to be working with some of the leading developers such as Mighty Bear, Crypto Raiders, First Light Games, and Legendary Play. If you’d like to learn more about how Nami can level up your web3 gaming project, please don’t hesitate to reach out! We’d love to hear from you.

To stay updated with our product launch and web3 gaming related discussions, come follow us on Twitter or hop on to our Discord.